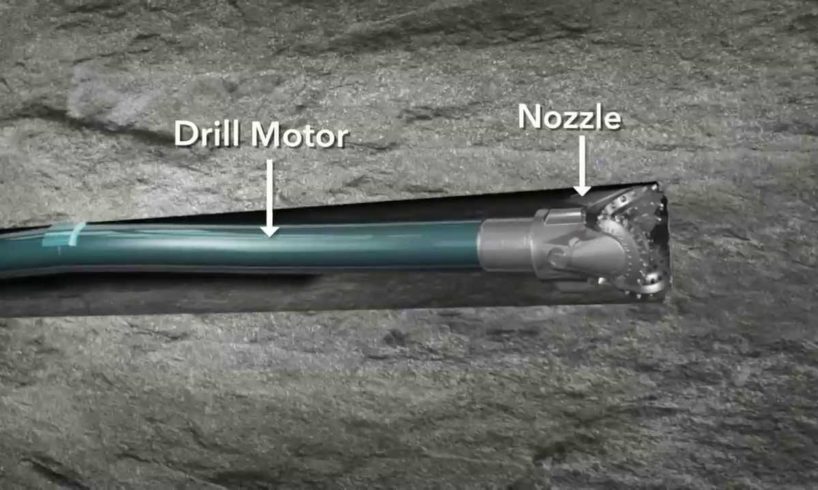

Horizontal Directional Drilling (HDD): How the Drill Bit is Steered

Horizontal Technology, Inc. (http://HorizontalTech.com)

888-556-5511 (toll-free)

Animation that shows how the drill bit is steered during the Horizontal Directional Drilling / Boring (HDD) process.

© Horizontal Technology, Inc. | All Rights Reserved

source

![Crazy, Near Death, and WTF Moments [Pt. 2] | Video Compilation 2024 | Fail Department](https://www.theviralist.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Crazy-Near-Death-and-WTF-Moments-Pt-2-Video-300x200.jpg)

Where does all the loose soil go ?

Imagine thousands of government sodomites hiding in their COG bunkers……

Bill Burdick is one of the number one people in the USA for Directional Drilling he owns DDC directional drilling company he's a legend in the industry

Lovely

But anyone here who can help me with either a video or manufacturer of a one metre diameter type of drill that can work on drilling out iron ores

Is Mike Rowe speaking?

Such an interesting technology.

What rotates the bit Downhole

kitne rupees 1meter

When you drill and case horizontally, how does the drill pipe and casing actually curve to achieve the 90 degree angle??

#INDIANTEEPEELOOKWHYOURESCUEDFORTHERETARTEDBRIISHFRENCHUSAWHOROBEEDVEITNAMKORIAIRAQEXSETTRATOPLAYKINGDINALINGSINTHENDISASETUPONALLOFTHECLWNSINCONGRESSWHOLIEDTOME

#ANCIETOUTOFDATEANTEQUSBORRINGISSOLIKECAPTINCAVEANDAYSDUFFICES#RETARTEDENGINEERING#DUMBASSLAWERS#GAYGOVERNMETSWEAKPARTYS#CLIMETTRACEFORMINGPOVERTY

Sector 2: ARTEMIS programs; (not yet finish);

(Platinum Golden Silver Surfer song: https://youtu.be/Fptue_EaMjw");

CODE: "QUEEN ALEX HOGAN";

Q-ueendoms

U-nlimited

E-xtended

E-xplorations

N-ASA

A-steroids

L-anders

E-xtraction

X-(J)-urisdiction

H-umanitarian

O-peration

G-lobal

A-llied

N-ations

OPERATION: "

Codename: "

Nickname: "

Whereas in Article 11 is particularly relevant to space mining. Asserts that U.S. citizens are “entitled to any asteroid resource or space resource obtained … in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of the United States.”;

3. THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL CONTEXT FOR ASTEROID MINING—THE

MOON AGREEMENT

As for the Moon Agreement, it was drafted with the intention partially

to also address possible commercial exploitation, as this seemed to lie

around the corner.28 Noting that it was never ratified by the major

juridical persons by such object or its component parts on the

Earth, in air space or in outer space, including the Moon and

other celestial bodies.

See also, e.g., Armel Kerrest & Lesley Jane Smith, Article VII, in 1 COLOGNE

COMMENTARY ON SPACE LAW, supra note 8, at 126, 129–145; VON DER DUNK, supra note

20, at 22–26.

26. Outer Space Treaty, supra note 10, Art. IX

If a State Party to the Treaty has reason to believe that an activity

or experiment planned by it or its nationals in outer space,

including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause

potentially harmful interference with activities of other States

Parties in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space,

including the Moon and other celestial bodies, it shall undertake

appropriate international consultations before proceeding with

any such activity or experiment.

See also, e.g., Sergio Marchisio, Article IX, in 1 COLOGNE COMMENTARY ON SPACE LAW,

supra note 8, at 169, 174–81; LOTTA VIIKARI, THE ENVIRONMENTAL ELEMENT IN SPACE

LAW 59–62 (2008); Howard A. Baker, Protection of the Outer Space Environment:

History and Analysis of Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty, in 12 ANNALS OF AIR &

SPACE L. 143, 166–67 (1987).

27. Cf., e.g., VIIKARI, supra note 25, at 59–60; Marchisio, supra note 25, at 176–

77.

28. Moon Agreement, supra note 12, Preamble (“Bearing in mind the benefits

which may be derived from the exploitation of the natural resources of the Moon and

other celestial bodies.”); id. art. 11(5) (“States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake

2017] Asteroid Mining: International and National Legal Aspects 89

spacefaring nations, it is nevertheless worthwhile to briefly discuss it

here since the original text was developed in agreement between major

spacefaring nations, including the United States.29

The Moon Agreement determined that the Moon, other celestial

bodies, and their natural resources were the “common heritage of

mankind” and called for an international regime to implement that

concept in the context of interests in mining operations30— without,

however, specifying any details.31 When, in the contemporaneous

discussions on the legal regime for the deep seabed resulting in the 1982

Convention on the Law of the Sea,32 the common heritage of mankind

concept came to be specifically elaborated as requiring the transfer of

relevant technology and the ultimate sharing of mining proceeds,33 the

to establish an international régime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the

exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become

feasible.”) (emphasis added).

29. Cf. Peter Jankowitsch, The Background and History of Space Law, in

HANDBOOK OF SPACE LAW, supra note 1, at 1, 5–6.

30. See Moon Agreement, supra note 12, art. 11(1) (“The moon and its natural

resources are the common heritage of mankind, which finds its expression in the

provisions of this Agreement and in particular in paragraph 5 of this article.”); Moon

Agreement, supra note 27, art. 11(5).

31. Id. art. 11(7).

The main purposes of the international regime to be established

shall include:

(a) The orderly and safe development of the natural resources of

the Moon;

(b) The rational management of those resources;

(c) The expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources;

(d) An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits

derived from those resources, whereby the interests and needs of

the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries

which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the

exploration of the moon, shall be given special consideration.

See also, e.g., CHRISTOL, supra note 9, at 342–63; FABIO TRONCHETTI, THE EXPLOITATION

OF NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE MOON AND OTHER CELESTIAL BODIES 41–61 (F.G. von

der Dunk, ed. 2009).

32. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea arts. 133–91, Dec. 10,

1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397.

33. See TRONCHETTI, supra note 30, at 45–61; LOTTA VIIKARI, FROM MANGANESE

NODULES TO LUNAR REGOLITH 52–54 (2002).

90 Michigan State ,QWHUQDWLRQDO/DZ5HYLHZ [Vol. 26.1

major spacefaring nations—including again the United States—refrained

from signing and ratifying it.34 The Moon Agreement, in spite of its

relatively limited formal importance, offers a few interesting aspects for

consideration with regards to the appropriate international legal approach

to space mining.

First, Article 1(1) in principle allows for a special regime in deviation

from the Moon Agreement, including for instance its application of the

common heritage of mankind concept, to be developed.35 If it would be

considered helpful and feasible to develop an international regime

specifically addressing the mining of asteroids, in a manner more

conducive to stimulating private entrepreneurship than the original

implementation of the common heritage of mankind concept in the

context of the Law of the Sea, then this clause allows that, even as far as

both the staunch adherents to that concept or parties to the Moon

Agreement would be concerned.

Second, it is interesting to note that the Moon Agreement itself

already excludes from its scope “extraterrestrial materials which reach

the surface of the earth by natural means.”36 While resources extracted by

mining companies obviously do not reach the surface of the Earth by

natural means, the distinction already made here between celestial bodies

and extraterrestrial materials is noteworthy. The asteroids targeted by the

space mining companies would likely be magnitudes smaller in size than

the celestial bodies usually addressed under that heading, such as the

Moon and planets. Landing on a celestial body would constitute a rather

different mission than landing on an asteroid, which may come much

closer to capturing extraterrestrial materials. The distinction made in the

Moon Agreement may provide further justification for the argument that

the prohibition to “appropriate” celestial bodies pursuant to Article II of

the Outer Space Treaty does not extend to extraterrestrial materials, the

34. See VIIKARI, supra note 32, at 68–72.

35. Moon Agreement, supra note 12, art. 1(1) (“The provisions of this

Agreement relating to the moon shall also apply to other celestial bodies within the solar

system, other than the earth, except in so far as specific legal norms enter into force with

respect to any of these celestial bodies.”).

36. Id. art 1(3). See, e.g., LYALL & LARSEN, supra note 8, at 175–77; Nicolas M.

Matte, Legal Principles Relating to the Moon, in 1 MANUAL ON SPACE LAW, supra note

10, at 253, 258.

2017] Asteroid Mining: International and National Legal Aspects 91

latter also referring to something magnitudes smaller than the classic

celestial bodies.37

Third, the common heritage of mankind principle may suggest some

mandatory sharing of benefits and technology as per the elaboration in

the context of the Law of the Sea, the Moon Agreement; it certainly does

not simply provide or confirm this. In building upon the general

prohibition of national appropriation in the Outer Space Treaty, namely,

it provides: “Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any

part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any

State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization,

national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural

person.”38 The addition of “in place” suggests that once extracted, such

resources could by contrast legitimately become the property of, for

instance, private operators. ; effective immediately;

(Contents); stated hereunder of;

1.) https://youtu.be/z6qVIIy0D5Y , ;🦊

2.) https://youtu.be/zSwdde4hd4Y , ;🦊

3.) https://youtu.be/HZPy8hH86LY , ;🦊

4.) https://youtu.be/cl8BBoCV7gU , ;🦊

5.) https://youtu.be/VrEUvzoNH9Q , ;🦊

6.) , ;🦊

7.) , ;🦊

Use this for geothermal power plant

Can anyone give me the drilling tools supplier details

informative

And when you fuk it up it looks like this: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/ER_8wt7CeuE

The Horizontal Directional Drill knows where it is at all times. It knows this because it knows where it isn't. By subtracting where it is from where it isn't, or where it isn't from where it is (whichever is greater), it obtains a difference, or deviation. The guidance subsystem uses deviations to generate corrective commands to drive the Horizontal Directional Drill from a position where it is to a position where it isn't, and arriving at a position where it wasn't, it now is. Consequently, the position where it is, is now the position that it wasn't, and it follows that the position that it was, is now the position that it isn't.

In the event that the position that it is in is not the position that it wasn't, the system has acquired a variation, the variation being the difference between where the Horizontal Directional Drill is, and where it wasn't. If variation is considered to be a significant factor, it too may be corrected by the GEA. However, the Horizontal Directional Drill must also know where it was.

The Horizontal Directional Drill guidance computer scenario works as follows. Because a variation has modified some of the information the Horizontal Directional Drill has obtained, it is not sure just where it is. However, it is sure where it isn't, within reason, and it knows where it was. It now subtracts where it should be from where it wasn't, or vice-versa, and by differentiating this from the algebraic sum of where it shouldn't be, and where it was, it is able to obtain the deviation and its variation, which is called error.

This movie is the best about horizontal directional drilling technology

「コンテンツを調整する必要があります」、

Hello

We are water well drilling rig machines producing it will be our proud to cooperate with you if you are interesting thanks

How do you get hdpe line tree hole

How do you get hdpe pipe threw

https://youtube.com/channel/UCbgPXIiaEnKnbTjClbhk2SQ

https://youtube.com/channel/UCbgPXIiaEnKnbTjClbhk2SQ

Pray to Rayan in morocco

The dyraulics

Yes it would be much faster.

But required some testing and simulations.

https://youtu.be/-zOZx9hx3MM

Happening on my street right now to install fiber backbone. Wondered how it worked and this explained it!